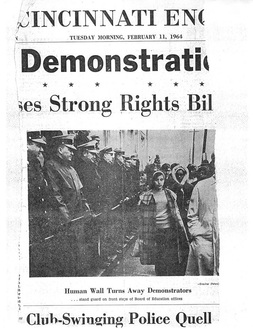

I’ve been teaching active duty and prospective police officers, as well as a diverse complement of others, for something over forty years now. This has included issues in policing as well as philosophies, administrative structures, models, and methods of policing. Indeed, at different points in my professional life I was invited to teach at the Ohio and New York Police Academies, but at those times there was no way I could have explained that to my friends and colleagues, so I declined the offers. I have also been on the advocacy side of the table, as you see from the back-in-the-day press pic, working with communities to establish civilian review boards, bringing police brutality to light, participating in direct challenges to abuses of policing authority, and, consequently, often being the target of police harassment myself.

I believe in the rule of law and in inclusive participatory governance, and that means believing in law enforcement and the making and implementation of the law in a fair and impartial manner. It is this belief that prompted so many of us to defy laws in the 50s and 60s that were in violation of these principles in order to insure that all citizens enjoy equal status and equal protection under our ultimate legal framework, the Constitution of the United States of America. Rules are necessary for people to live together in groups; indeed, most social scientists would say that “society” began with the first rule—with the first group of humans whose members said, “I’m willing to give up some of my individual freedom so that I can enjoy the protection, productivity, and communion of the group.” Whether one shares a “Lockeian” or “Hobbesian” vision of this scenario, the social contract emerged at some point in our evolution, and has framed the course of human development ever since, with an almost infinite variety of outcomes.

So, with the exception of those who would like to live unrestrained (which, ironically enough, would require restraining others), most of us understand that rules are necessary, and that rules are meaningless unless they are enforced—at least, until we humans reach that nirvana in which we all know what the rules are and follow them voluntarily, because we have internalized the idea that it’s the right thing to do. (This being “pure communism” in modern ideology, although actualized by many indigenous peoples prior to conquest by Anglo-Europeans, but that’s a different conversation.) The practical issue isn’t whether “law” or “law enforcement” is evil and should be done away with, but how to make just law and enforce it with wisdom and equanimity. That means electing policymakers who hold and will apply civic values to their legislative and administrative roles, acting in the public interest and supporting PDs that work hard to earn and maintain the trust and cooperation of the communities they serve. There are a lot more of those than the U.S. media would have us believe, including metro police chiefs and county sheriffs with integrity who have outright refused to follow the directives of Homeland Security and Immigration "authorities."

A few years ago I was asked to design and teach a course in “Policing and Civil Society” by Eastern Kentucky University’s College of Justice and Safety, which I did, and have been teaching it ever since. It has been one of the most gratifying teaching experiences of my life, both in the quality and thoughtfulness of students’ work, and in the positive feedback I’ve received in formal course evaluations. Learning about policing from both sides of police-citizen encounters, and the comparative impact on communities of different policing styles, has made a huge difference in the outlooks and imaginations of not only the current and prospective cops who take these courses, but the array of community residents and other service professionals who also enroll in the class.

In short, I am doing my share to promote system change in this particular area of social concern by teaching current and prospective police and corrections officers and administrators alternative perspectives on and approaches to their professional practices and the policy issues they will continue to confront. So, for what it’s worth (as, if social media is any indication, fewer and fewer people seem to care what’s true any more), here are some things I have learned over all these years:

• As in any profession, there are good cops and bad cops and lots of shades in between. Unlike most other professions, however, those shades can be a matter of life and death, whether for co-workers inside "the system" or victims and bystanders outside, much as they are in corrections and the military, which are confronting similar issues regarding unrestrained violence with few if any repercussions. I believe most of us agree that wanton, unrestrained, arbitrary violence whether on the parts of those sworn to uphold the law or the lawless predators who stalk many of our communities has no place in a civilized society, or in one that purports to be dedicated to principles of democracy and the rule of law.

• There are, indeed, brutal, blood-lusting abusers of their authorization to be judge, jury, and executioner, who gleefully take out their hatred of “the other,” be they black, brown, gay, female, “foreign,” or multiples of the above, not to mention perceived challenges to their masculinity, who arbitrarily harass, maim, rape, and/or kill their vulnerable victims. With the collusion and support of “sympathetic” administrators, prosecutors, and judges, their behavior is routinely reinforced rather than suppressed in far too many jurisdictions. (The Vic Mackey character in the FX series The Shield is a great example of this.)

• There are also those in blue that go the extra mile for victims, residents, shopkeepers, and passers-by, who are genuinely dedicated to “serving and protecting” in the most honorable sense of the phrase. These tend to suffer a lot of grief from both their “masculinist” colleagues and a myopic public, but also experience heartfelt appreciation from those who benefit from their prompt, considered attention, their respect, and their effectiveness in the streets. They are focused on the “peace officer” aspect of the job, and work and study hard to live it in the everyday practice of their profession. (The Jamie Reagan character in the CBS network series Blue Bloods is a great example of this.)

• Administrators—from front-line supervisors to Chief to whatever politico appoints the Chief—are the key determinant as to which mode dominates any particular department or jurisdiction. The policies they promote and enforce, both formal and informal, send the signals to the troops as to what behaviors will be rewarded or punished, tolerated or prohibited. Political processes put these individuals in place and give them their authority; political processes can replace repressive institutional policies and personnel with community-responsive ones.

• Civilian review boards and community policing modalities, when structured and implemented in ways found to be effective, are two strategies that have been successful at building trust and cooperation on both sides of the thin blue line. “Get tough” policies and the (euphemistic) “war on drugs” have done more to inflame police-community tensions and prompt violence in the streets than any other identifiable factors in this devolution.

• The demilitarization of PDs is crucial to any improvement in police-community relations across the country. We have PDs that have been trying to give back military equipment and weaponry that has been forced on them, that they have no intention of using, but that they have to bear the ongoing costs of storing and maintaining, and finding that they are unable to do so! Others are using it to escalate the aggressive control of minority and low income communities, fueling tensions and inviting retaliation in self defense. The most horrific example of where this is going is the use of an armed drone to blow up a suspect in a Dallas shooting case.

If I were to prepare a starter reading list for people genuinely interested in addressing critical issues in police-community relations in the U.S. (as opposed to running their mouths with a bunch of knee-jerk rhetoric), it would look like this:

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow

Jimmy Breslin, World Without End, Amen

Elliot Liebow, Tally’s Corner

Peter Maas, Serpico

Michael Palmiotto, Community Policing: A Police-Citizen Partnership

Richard Price, Clockers

Jonathan Wender, Policing and the Poetics of Everyday Life

Once you get all this under your belt, let’s talk.

Deb Louis

Micaville, NC • July 9, 2016